Stefan Löfven should have savored Sunday night — as Sweden’s election results came in, his center-left Sveriges socialdemokratiska arbetareparti (Swedish Social Democratic Party) emerged as the top vote-winner by an 8% margin, and Löfven is the overwhelming favorite to become Sweden’s next prime minister.![]()

Monday morning was a different story.

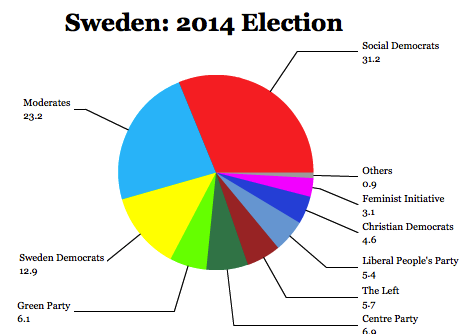

Despite winning the election, the Social Democrats won just 31.2% of the vote, a relatively low total for the party that dominated Swedish government throughout much of the 20th century. In the last two elections, in 2006 and 2010, when outgoing prime minister Frederik Reinfeldt routed the Social Democrats, the party still won 35.0% and 30.7%, respectively.

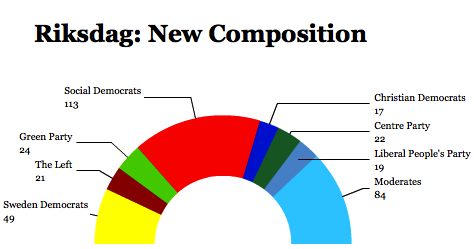

The last time they won an election, under Göran Persson in 2002, the Social Democrats won 39.9% of the vote. The results from September 14, however, leave Löfven (pictured above) with just 113 seats in the 349-member Riksdag, Sweden’s unicameral parliament.

If the big loser of the election was Reinfeldt’s center-right Moderata samlingspartiet (Moderate Party), which lost 23 seats, the big winner was the far-right, anti-immigrant Sverigedemokraterna (SD, Sweden Democrats), which gained 29 seats on a platform of limiting Sweden’s generous asylum policy that in 2014 is expected to welcome more than 100,000 refugees to the country, many from war-torn Syria and Iraq. It’s a point of pride for Reinfeldt, presumably, that he spent much of the campaign extolling the compassionate values of his government, even if those costs limited his ability to promise greater welfare spending.

If the big loser of the election was Reinfeldt’s center-right Moderata samlingspartiet (Moderate Party), which lost 23 seats, the big winner was the far-right, anti-immigrant Sverigedemokraterna (SD, Sweden Democrats), which gained 29 seats on a platform of limiting Sweden’s generous asylum policy that in 2014 is expected to welcome more than 100,000 refugees to the country, many from war-torn Syria and Iraq. It’s a point of pride for Reinfeldt, presumably, that he spent much of the campaign extolling the compassionate values of his government, even if those costs limited his ability to promise greater welfare spending.

The rest of Sweden’s parties all made relatively small gains or losses — no other party gained or lost more than five seats in total.

* * * * *

RELATED: Swedish far-right could inadvertently deliver

3rd term to Reinfeldt

RELATED: One month out, Löfven and Social Democrats lead in Sweden

* * * * *

Those dynamics, however, leave Löfven in an unenviable position. Though the Sweden Democrats have clearly made the greatest gains in this election, neither the Reinfeldt-led center-right nor the Löfven center-left are willing to bring the anti-immigrant party into government, despite the efforts of its boyish leader, Jimmie Åkesson, to moderate the party’s harder nationalist (and sometimes neo-nazi and xenophobic) edges. One marvels to wonder his well his party might have done had it not been dogged by scandals that forced eight candidates out of the race after news outlets revealed their racist online commentary.

A hung parliament — and no majority for Sweden’s left

But that’s left the Riksdag without a clear majority. After the 2010 elections, the Moderates and their three allies, which together constitute the Alliansen, formed a minority government with 172 seats. Unofficially, the Swedish Democrats often delivered enough votes for Reinfeldt to fill the three-vote gap that his government needed. Löfven cannot count on the unofficial support of Åkesson’s right-wingers. Moreover, after the stunning results for the Sweden Democrats, there are now 49 seats, not 20, that are politically untouchable.

Löfven’s most natural allies, the Miljöpartiet (Green Party), actually lost a seat, falling to 21 seats. Together, with 134 seats, that leaves the Red-Green coalition 41 seats short of a majority.

Even if he wanted, Löfven couldn’t find those seats looking leftward. The presumptive prime minister on Monday ruled out a formal coalition with Sweden’s most leftist party in the Riksdag, the Vänsterpartiet (Left Party). A formal alliance with the Left Party during the 2010 campaign left voters and markets wary of the Social Democrats, one factor that resulted in their defeat. But with just 21 seats, a three-way Red-Green coalition would still leave Löfven 17 seats short of a majority — and likely push the defeated four center-right Alliansen parties closer together in opposition against a weak government. One of the problems is that just over 3% of the Swedish electorate backed the Feministiskt initiative (Feminist Initiative), a unique women’s right party that attracts international attention. Strategically, however, the Feminist Initiative fell just short of the 4% threshold to win seats in the Riksdag. From the Social Democratic perspective, that 3% of the electorate could have boosted a stronger showing for the other three leftist parties, which now find themselves short of a majority and with few natural allies.

In some ways, it’s surprising than Reinfeldt so quickly conceded defeat and announced that he would stand down from the Moderate leadership. Together, the Alliansen has 142 seats — more than the Social Democrats and Greens together — and with outside support from the Sweden Democrats, might form a more credible minority government than Löfven.

It’s a defeat that has repercussions across the European Union. British prime minister David Cameron will have lost in Reinfeldt a center-right ally from a non-eurozone country that supports Cameron’s EU reform agenda. German chancellor Angela Merkel has lost a champion of center-right economic reform to a government more allied to the pro-growth governments of French president François Hollande and Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi. Eastern Europeans will regret the loss of Carl Bildt, a former prime minister and foreign minister since 2006, one of the leading European architects of the united strategy against Russia’s most recent steps.

A turn to the middle

Instead, Löfven hopes he can peel off at least two of Reinfeldt’s three allies — probably the liberal, urban-based Folkpartiet liberalerna (Liberal People’s Party) and the libertarian, rural-based Centerpartiet (Centre Party).

It won’t help that in the final days of the campaign, Löfven was seen shoving aside the Centre Party’s leader, Annie Lööf, during a debate. Lööf (pictured above), the 31-year-old outgoing minister for enterprise, has put a more liberal imprimatur on a party with agrarian roots that traditionally focused on environmental and farming issues.

Notwithstanding the brouhaha surrounding the Löfven-Lööf confrontation, she’s a rising star who in 2012 criticized the current government for its inability to renew the reformist zeal that propelled it to power in 2006, when Lööf, at age 23, was first elected to the Riksdag. Though all four parties in the Alliansen lost seats, her Centre Party lost just one (fewer than the others), and its historical emphasis on green issues could make it a good fit in the kind of broad liberal, center-left coalition that Löfven now wants to build.

The Centre Party has just 22 seats, which means Löfven will also need to woo Jan Björklund, the leader of the Liberal People’s Party. The outgoing deputy prime minister since 2010 and the education minister since 2007, Björklund would be an unlikely Löfven ally at first glance. As education minister, he’s championed reforms instituted in 2012, and both Reinfeldt and Björklund suffered from reforms introduced in the 1990s to privatize many secondary Swedish schools, especially after several private-sector companies have fallen short of public standards.

A former army major, Björklund was a supporter of the US-initiated invasion of Iraq in 2003, and he supports (like Finland’s new prime minister Alexander Stubb) joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

For now, both Björklund and Lööf say they will remain in opposition and it’s hard to see exactly how Löfven would pull together a centrist coalition that would embrace two of Reinfeldt’s former allies. Supporters and Reinfeldt’s Moderates might howl if Björklund and Lööf immediately make a 180-degree turn from a center-right government to a center-left government. But the outgoing prime minister’s resignation makes those negotiations less awkward by conceding that a post-Reinfeldt moment has arrived in Sweden. (The most audacious government of all would be a Social Democrat-Moderate ‘grand coalition’ of the kind that currently governs Germany, Austria and The Netherlands).

It would seem that there’s room enough for negotiation with two small, economically liberal parties. Löfven and his presumptive finance minister, Magdalena Andersson, an economist and the former director of the Swedish Tax Agency, have tried to demonstrate that they want to make only incremental changes to the Swedish budget.

Faced with the pressure of giving Sweden a stable government that continues to isolate the far-right SD, the Centre Party and the Liberal People’s Party might stand to gain respect by teaming up with Löfven, especially if they can credibly say that they pulled Sweden’s budget toward the center.

Moreover, at a time when Russian aggression has left all of Europe rethinking security policy, it would hardly be a concession for Löfven to promise Björklund ever closer ties with NATO — it’s something both the Swedish and Finnish governments are already doing.

It’s a government that investors would love — a majority coalition that, by design, will keep the most statist instincts of the Social Democrats and Greens in check. Löfven will be under pressure to maintain economic growth that’s outpaced both the United States and the rest of the European Union, while bringing down Sweden’s high unemployment rate, which is still hovering at around 8%. Bringing in the Centre and Liberal People’s Parties would help show that the next Swedish government represents continuity as much as change.

But it’s a tall order, especially for a leader like Löfven, a former metalworkers’ union leader who has no parliamentary experience, though he negotiated tough deals cutting hours and instituting pay freezes on behalf of IF Metall, Sweden’s largest metalworkers union.

If Löfven fails, he’ll have to smooth over the ruffled feelings of the Left Party’s leader Jonas Sjöstedt (pictured above), who has railed against the increasing privatization of Sweden’s public sector in the past two decades:

“The Social Democrats had a choice to rule toward the left or toward the right and they chose the right,” Left party leader Jonas Sjöstedt said. TT news agency reported he was visibly agitated and said “Social Democrats are making a huge mistake.” Sjöstedt said he could still support Löfven from the outside, especially for the budget, only if the Social Democrats agree to restrict how private companies run state hospitals and schools, one of the most far-reaching reforms of recent years.

With just 158 votes among the three parties, Löfven might be hard-pressed to pass his first budget later this year, which could precipitate fresh elections or greater political uncertainty.

That explains why Löfven is seeking a much stronger government — even if he has to make serious compromises to get there.