Amid the chaotic urban anarchy of Karachi and the lawlessness of tribal border areas near Afghanistan, it’s rare that Islamabad becomes the central focus of political instability in Pakistan.![]()

But that’s exactly what’s happening this week in the world’s sixth-most populous country, and if protests against Pakistani prime minister Nawaz Sharif explode into further unrest, it could trigger a constitutional crisis or even a military coup. That Pakistan’s fate is now so perilous represents a serious step backwards for a country that, just last year, marked the completion of its first full five-year term of civilian government and a democratic transfer of power.

Imran Khan (pictured above), the leader of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI, پاکستان تحريک انصاف, translated as the Pakistan Movement for Justice), is leading protests in the Pakistani capital calling for Sharif’s resignation relating to allegations of voter fraud in last year’s national elections. Sharif, in turn, is pressuring the country’s powerful military to guarantee order in Islamabad and the ‘red zone’ — a highly fortified neighborhood where many international embassies and the prime minister’s house are located and where Khan and his supporters have threatened to march if Sharif refuses to step down. Khan has increasingly escalated his demands, and he now seems locked in a high-stakes political struggle with Sharif that could end either or both of their careers.

In last May’s parliamentary elections, Sharif’s conservative, Punjab-based Pakistan Muslim League (N) (PML-N, اکستان مسلم لیگ ن) ousted the governing center-left, Sindh-based Pakistan People’s Party (PPP, پاکستان پیپلز پارٹی). Khan’s anti-corruption party, the PTI, won 35 seats, the second-largest share of the vote nationally, and the largest share of the vote in regional elections in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the northwestern border region near Afghanistan that is home to nearly 22 million Pakistanis, largely on the strength of Khan’s denunciation of US drone strikes on the region. Though Khan and the PTI hoped for a better result, it was nevertheless their best result by far since Khan entered politics in 1996.

Earlier this week, Khan directed his party’s legislators to resign from of the national assembly and three of the four regional assemblies. (The PTI wouldn’t, after all, be resigning its seats in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where it controls the government).

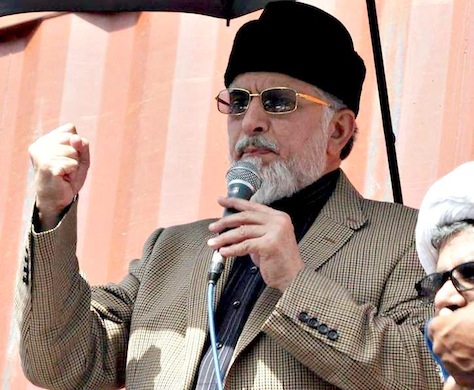

Khan’s protests dovetail with similar protests led by Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri (pictured above), a Sufi cleric and scholar who leads a small but influential party, the Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT, پاکستان عوامي تحريک, translated as the Pakistan People’s Movement). Like Khan’s PTI, the PAT is an anti-corruption and pro-democratic party. Tahir-ul-Qadri, who returned to Pakistan in 2012 after living for seven years in Toronto, has been described as the ‘Anna Hazare’ of Pakistan, in reference to the Hindu social activist who’s fought against corruption in India, and he protested the PPP with equal gusto.

Early Thursday, there were hopes that negotiations among the parties could relieve the political crisis’s escalation, if not wholly end it. But it’s more complicated that, because of the delicate role that the military still plays in the country’s affairs.

You can think of the current tensions in Pakistan as a triangular relationship:

- Nawaz Sharif and the civilian government. Sharif (pictured above), as the leader of the civilian government, is pushing the military to defend his administration by guaranteeing order in the event that opposition protests get out of control. Sharif should know the limits of civilian government — he was ousted and exiled after the military coup in 1999 that brought Pervez Musharraf to power. His brother, Shahbaz Sharif, is the chief minister of Punjab, the country’s largest and most populous province, and has served as a key conduit between Sharif’s national government, on the one hand, and the military and opposition, on the other hand.

- Raheel Sharif and the national army. The military is under the command of army chief of staff Raheel Sharif (pictured above), appointed by Sharif (no relation) late last year, and less reticent than his predecessor Ashfaq Pervaiz Kayani to intervene in political matters. While the military, since the end of Musharraf’s military rule in early 2008, has largely receded from politics, its leaders don’t particularly welcome Nawaz Sharif’s attempt to bring it into the middle of the current showdown, and military leaders have cautioned both the government and the opposition in the last week. Before the latest political confrontation, Nawaz Sharif was already at odds with the military over the ongoing Musharraf trial, an attempt to broker peace talks with the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (Pakistani Taliban) and his attendance at the swearing-in of India’s new prime minister Narendra Modi. By weakening the government, Khan’s protests risk strengthening the military vis-à-vis civilian officials.

- Imran Khan and the opposition protesters. Though Khan would like to believe himself the champion of Pakistani democracy, he’s increasingly seen as a demagogue and a grandstander, a view that’s only widened since last year’s election. Despite his calls for Sharif’s resignation, it took him 15 months to decide that he would reject the 2013 elections, making his protest seem based more on convenience than conviction. He also knows that by destabilizing Islamabad, he could be pave the way for further military intervention. That’s hardly the responsible actions of a committed democrat.

But even as the protests continue, the fundamental question lingers — were last year’s elections rigged?

There are solid arguments in each case.

In Sharif’s defense, the outgoing PPP government was widely despised in light of the perceived incompetence, impotence and outright corruption of the PPP’s titular leader, former president Asif Ali Zardari, the widower of the late Benazir Bhutto. Their son, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, the rising hope of the party’s future, is just 25 years old, and he allegedly spent much of last year’s campaign in Dubai. It’s convincing that, on the basis of the PML-N’s support in Punjab, it won a landslide mandate last year. Though the extent of Sharif’s victory was perhaps a surprise, it’s hard to believe that Sharif’s allies falsified enough voters to conjure a landslide. Despite the PTI campaign, it’s credible to believe that it lacked the patronage network and party machine to contest the PML-N in a serious manner in Punjab. That might not amount to a fair election, but that’s not the same as widespread voter fraud.

Nevertheless, there are concerning elements to last year’s voting. Pakistan doesn’t have a spotless democratic history, there were widespread reports of fraud in the country’s financial center and largest city, Karachi. A joint report from the US-based National Democratic Institute and the Asian Network for Free Elections outlines many areas for improvement without alleging the kind of widespread fraud that Khan and his allies allege.