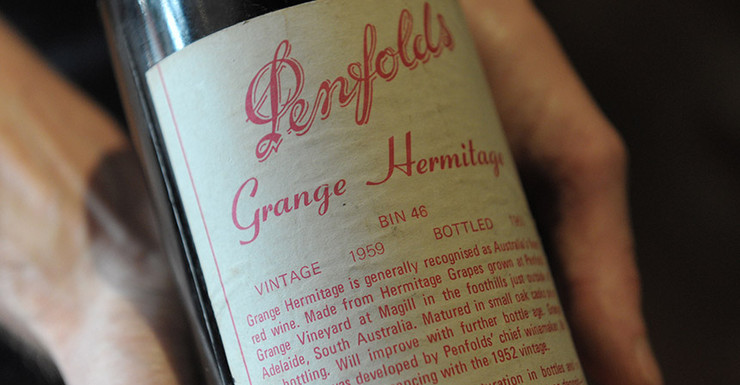

In the end, all it took for Barry O’Farrell to lose his job as the premier of New South Wales, Australia’s most-populous state, was a $3,000 bottle of wine.![]()

![]()

Though he came to power in 2011 in a landslide victory over the Australian Labor Party, O’Farrell resigned last week as premier after just three years in office and seven years leading the NSW division of Australia’s center-right Liberal Party.

O’Farrell, who appeared before the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC), denied having received a gift bottle of 1959 Grange Meritage from from an executive at Australian Water Holdings. Unfortunately for him, the commission had found a handwritten thank-you note to AWH’s CEO Nick Di Girolamo, which read:

Dear Nick & Jodie, We wanted to thank you for your kind note & the wonderful wine. 1959 was a very good year, even if it is getting even further away! Thanks for all your support. Kind regards, Baz & Rosemary.

A day after the thank-you note came to light, O’Farrell (pictured above) claimed that, in a ‘massive memory fail,’ he had no recollection of the gift, but nevertheless announced his resignation. He stepped down officially on Thursday, and the New South Wales treasurer Mike Baird became the state’s new premier the same day.

It’s a fairly well-trodden path for a politician caught in a bind like this — if you believe your position untenable, better to resign as early as possible, take credit for ‘falling on your own sword,’ and hope for future rehabilitation via the private sector or, in time, a political sinecure. Sure enough, at the end of the week, Liberal prime minister Tony Abbott was praising O’Farrell for having ‘taken the honorable step’ of resigning.

O’Farrell’s resignation came so fast that some commentators wondered whether he did so because he realized more revelations would come out through the commission’s investigation.

In political terms, his resignation is unlikely to dent Abbott’s Liberal/National Coalition government. But it turns state politics upside down in New South Wales, home to 7.3 million Australians — nearly one-third of the country’s entire population.

If anything, the sensational turnabout might make life marginally easier for Abbott, who has always been personally and politically closer to Baird. O’Farrell has always been more moderate that Abbott, especially on social policy. For example, O’Farrell worked with former Labor prime minister Julia Gillard to sign up to federal national education reforms and to sign up for the rollout of its national disability insurance scheme. In both cases, New South Wales — under Liberal rule — was the first Australian state to do so.

O’Farrell also came out in support of same-sex marriage in 2013, putting him in conflict with Abbott, who opposes it. After Abbott won power in last September’s national elections, O’Farrell called on Abbott to allow a ‘conscience vote’ in Australia’s national parliament on the matter.

Though the Liberals now control 69 out of 93 seats in the Legislative Assembly, the lower house of the NSW parliament, O’Farrell never really pushed the bold agenda you might expect for a premier with a Liberal supermajority in New South Wales:

Something that can never be taken away from O’Farrell is that he led the Coalition out of the wilderness of opposition after 16 years.

But there will be more than a few of its members who are pleased he has gone. To them it seemed the longer he remained Premier the more cautious and less effective he became. Ironically, many believed the approach was aimed at ensuring his own longevity in office.

In contrast, Baird seems prepared to push for major GST (goods and sales tax) reforms almost immediately.

O’Farrell is not the first premier to fall to the ICAC — Liberal Nick Greiner, NSW premier between 1988 and 1992, established the commission in 1989, and it proved to be his undoing. The ICAC ultimately brought to light improprieties in the hiring process for an executive in the state’s environmental protection authority. That ultimately led to Greiner’s resignation when it became clear he couldn’t win a no-confidence vote in the NSW legislative assembly.

Top photo credit to AAP, bottom photo credit to News Limited.