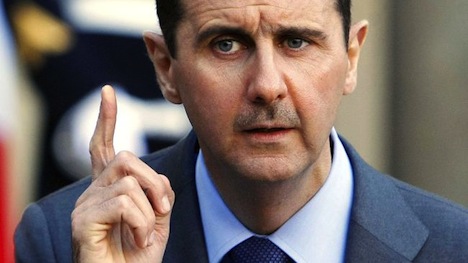

The US Senate, the upper chamber of the US Congress, held hearings Tuesday that included testimony from US secretary of state John Kerry and US defense secretary Chuck Hagel in support of the use of force to punish Syrian president Bashar al-Assad for the use of chemical weapons in Syria two weeks ago.![]()

![]()

![]()

But even though US president Barack Obama announced over the weekend that he will not launch any military strike against Syria without congressional support — a potentially historic concession from the executive branch of the US government to the legislative branch — there are still more questions than answers from the Obama administration as it now enlists Congress in its mission against Assad.

The US Congress can — and should — push Obama, Kerry, Hagel and others for answers to two general sets of issues, especially with a second round of classified hearings set to take place Wednesday.

The first issue involves discovering the hard facts of what actually happened on in Ghouta and on the eastern outskirts of Damascus on August 21. The second issue is what the United States can (and should) do that will most effectively deter the use of chemical weapons in the future. Even though the dominant narrative is now the congressional vote on US military action in Syria in particular, confirming answers to the first set of issues is a threshold requirement for exploring the second set of issues.

Even as House speaker John Boehner, House minority leader Nancy Pelosi and other top leaders in both the Republican Party and the Democratic Party move to close ranks around the Obama administration, and as hawks like US senator John McCain of Arizona push for an even stronger response that embraces the goal of regime change in Syria, it’s even more important to push for answers.

Here are 10 questions that rank-and-file congressional members, the media and the US public should be asking between now and next week’s vote:

1. Who is to blame for the chemical attack?

Despite the fact that Kerry released a 1,434-word ‘government assessment’ last Friday that purports to implicate Assad for the chemical attack, it’s not really all that convincing.

The White House ‘assesses with high confidence that the Syrian government carried out a chemical weapons attack,’ killing 1,429 Syrians (including 426 children). It alleges that ‘there is a substantial body of information that implicates the Syrian government’s responsibility’ in the attack, there’s very little new information in the assessment, which relies heavily on existing circumstantial facts — that the Syrian regime maintains a stockpile of chemical agents, that Assad is the ultimate decision-maker for Syria’s chemical weapons program, and that the Syrian regime has the types of munitions that the US government believes were used in the attack.

The assessment concludes that ‘regime officials’ directed the attack on the basis of ‘past Syrian practice’ as well as new intelligence. But who, exactly, counts as a ‘regime official’ in the Syrian army these days? The US government intercepted communications ‘involving a senior official intimately familiar with the offensive’ who apparently confirmed that the Assad regime was responsible. But who was the senior official? And if this is the ‘smoking gun’ that ties Assad to the attack, why isn’t it public? Does it come from US intelligence or from Israeli intelligence? The assessment adds that the US government has intelligence that ‘Syrian chemical weapons personnel were directed to cease operations’ on the afternoon of August 21, but that’s entirely consistent with an attack launched by rogue elements within the Syrian army.

It doesn’t assess that Assad — or any of his top aides — ordered the attack. It doesn’t assess whether the attack was deliberate or accidental. It leaves open the possibility that rogue pro-Assad elements may have launched the chemical attack without Assad’s knowledge or approval — and it also leaves open the possibility that anti-Assad rebels obtained chemical weapons and unleashed them, perhaps even mistakenly, on Syrian civilians, though the assessment concludes that is ‘highly unlikely.’

That’s it.

For over a week now, since Kerry’s first statement on the matter August 26, the US government’s position on Assad’s culpability has been essentially, ‘trust us — we know he did it,’ but the dossier released last Friday falls far short of Kerry’s certainty.

We also know, after the lead-up to the Iraq War in 2002 and 2003, of the fierce incentives driving US intelligence agencies to produce material that corroborates existing suspicions. We also know that our allies can produce faulty evidence or have motives that aren’t wholly driven by what’s in the US national interest. You can assume that the Obama administration and the American apparatus of military and civilian intelligence is working in good faith while still acknowledging that the past practice of former US administrations (and not just in Iraq — think of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, the Iran-Contra affair and so on) is enough to justify the public release of as much of the raw intelligence material as possible.

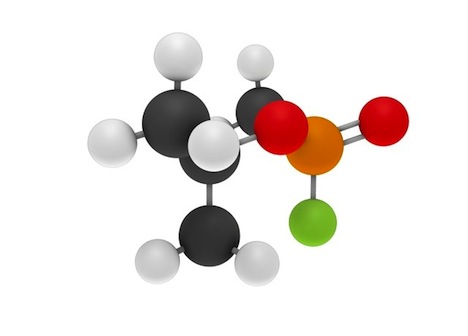

2. Which chemical agent was used in the attack?

It’s clear that a very deadly poison killed many Damascenes early in the morning of August 21. But it’s imperative that the US public know as much as possible about what actually happened before the US Congress and the Obama administration approve military intervention.

It’s clear that a very deadly poison killed many Damascenes early in the morning of August 21. But it’s imperative that the US public know as much as possible about what actually happened before the US Congress and the Obama administration approve military intervention.

On Sunday, Kerry announced that the United States determined the presence of sarin in the Ghouta attacks, on the basis of hair and blood samples that US intelligence agents obtained from sources within Syria — independent of the United Nations inspectors who visited the site of the attack late last week. But without impugning the integrity or competence of the Obama administration, is it not too much to ask for the United States to wait for the report of United Nations weapons inspectors who actually toured the site of the chemical attack?

If the Obama administration can hold off on military strikes for nearly two weeks in order to allow a congressional vote, certainly it can wait for the full UN report on what happened on August 21 — if the weapons inspectors confirm the presence of sarin, corroborate the US assessment’s death count, and detail any additional information about the attack and how it happened, it can only bolster the American case for intervention.

3. Why shouldn’t the United States exhaust non-military options before launching missiles into Syria?

OK, so let’s say that the Obama administration can put together a foolproof case that Assad is clearly culpable for chemical warfare. He’s breached nearly a century of international law and custom in resorting to the use of chemical weapons. As Kerry noted on Tuesday, that means Assad has not only crossed Obama’s ‘red line,’ but he has crossed the ‘red line’ that history and decency have already established. He used a horrific nerve agent to deliver a terrifying and undignified death to civilians, including many women and children. It’s the act of a monster who has arguably forfeited any claim to power.

But why is US military intervention the only possibility? There are any number of options, including tightening the economic and diplomatic sanctions against Assad or working to convince Russia to stop selling arms to Assad (perhaps through a sweet oil deal between US ally Saudi Arabia and Russia?). But the clearest option that no one in the Obama administration is talking about is an indictment of Assad and other Syrian military leaders at the International Criminal Court. It would require Russia’s tacit approval, but why not start drumming for Assad’s ICC prosecution? If the United States can debate launching military strikes without Security Council authorization, why can’t ICC prosecutors start putting a case together against Assad and his cronies?

4. Why shouldn’t the United States exhaust negotiations at the United Nations and the Security Council?

In his remarks on Saturday announcing that he would put the question of US military intervention to the US Congress, Obama made clear that he has no patience for what he called the ‘completely paralyzed’ Security Council.

But why? Where’s the international law that says you can ignore the Security Council just because you’ve run out of patience with Russia? Only two years ago, the Security Council approved the use of force against former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi when he started gunning down Libyan protesters during the 2011 Arab Spring (Russia and China, two of the five permanent members of the Security Council abstained from the Libya vote, therefore allowing the other members o the Security Council to proceed). The Libya action proves that the Security Council isn’t nearly as paralyzed as Obama believes.

Moreover, UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon (pictured above) correctly noted on Tuesday that a unilateral US military strike against Syria, even with the support of France, Australia, Turkey or other European or Arab nations, would still be illegal under international law:

“The use of force is lawful only when in exercise of self-defense,” Ban said during a news conference at UN headquarters in New York, “or when the Security Council approves such action.”

Given the blurriness of international legal doctrines, that may not be so important to the Obama administration — after all, Bill Clinton’s administration got pretty comfortable with the Kosovo intervention in 1999 for several reasons, but it’s hard to escape the conclusion that it was illegal as far as the United Nations and international law goes. But if your goal is to punish the Syrian regime for infringing an international legal norm, there’s a strong case that you should at least go through the motions of international legal process before you decide to punish the Syrian regime for its transgression.

5. How much should the United States trust the anti-Assad opposition?

This is one question that American politicians — right, left and middle — are asking in very sharp terms.

It’s important, because the chiefly Sunni opposition is a mixed bag of everything from former Syrian army commanders to radical Islamic jihadists. McCain, especially, has advocated that the United States aggressively support Syria’s opposition. But as every policymaker now knows, the Syrian opposition isn’t just the relatively moderate and secular Free Syria Army (the Farouq Brigades, a group within the Free Syria Army, are responsible for some of the most alarming headlines over the past two years). An attempt to cobble together an alternative anti-Assad Syrian coalition government has been largely unsuccessful. The Sunni group Jabhat al-Nusra, a radical al-Qaeda affiliate, is working against Assad as well, even though the United States has designated it as a terrorist organization. The Syrian Islamic Front is an even larger umbrella group of Salafist fighters who support the introduction of sharia law in Syria.

So supporting the opposition is a roll of the dice — there’s no guarantee that a Sunni government in Syria would be any better than the Assad regime. Is it preferable that a government sympathetic to al-Qaeda has access to Syria’s chemical weapons?

Consider the example of Mali — the initial uprising in early 2012 originated with the Tuareg separatist movement. But the power vacuum that their uprising created (and the subsequent military coup in Bamako), provided opportunities for homegrown Islamists groups like Ansar Dine and international Sunni jihadists close to al-Qaeda to dominate northern Mali for a year and institute sharia law from Timbuktu to Gao.

6. What happens if the United States kills even more civilians with a military strike?

Ezra Klein asked this very question at The Washington Post‘s Wonkblog last week — if the US military launches missiles at Syria, there’s certainly a good chance that those strikes will kill innocent civilians and that the Syrian regime might even maximize the death toll among those civilians:

The United States has been very clear that this is not a mission to save civilian lives. It’s a mission to enforce international norms against the use of chemical weapons. Rather than protecting civilians from being killed, we are attempting to alter Assad’s choice of weaponry when he kills them. It’s entirely plausible that Assad could heed our message to stop killing civilians with chemical weapons even as he heeds his incentives to retain control of the conflict by stepping up his slaughter of civilians through more conventional means. That would, on some perverse level, be a ‘success’ given the main goal of the policy, but it would be an awful failure on a humanitarian level.

How many civilian deaths are ‘acceptable’ to the US government during a punitive strike? Less than 1,400? More? Who’s capable of making that kind of calculation? That’s even aside from the question of whether military interventions save lives at all, an issue that Erica Chenoweth took up last week at The Monkey Cage (it’s also worth taking a look at some of the commentary at the blog she co-authors, Political Violence @ a Glance).

There are good reasons for the United States and the international community to uphold the international norm against chemical warfare, but this question hints at the awful arithmetic of Syria’s civil war. Nearly 100,000 Syrians have died in over two years of civil war so far. But is it so clear that the 1,400 sarin-related deaths on August 21 merit the kind of international force than 100,000 deaths from conventional weapons did not? What if it’s, say, 800,000 deaths over three months?

7. Are there smarter ways to deploy force in Syria than just lobbing missiles?

Another way to ask this question is, ‘why wouldn’t a NATO-led, UN-approved no-fly zone work more effectively at reducing the Assad regime’s ability to maneuver and, therefore, restrict its ability to unleash either conventional or chemical weapons on Syrian civilians?’

US lawmakers are already asking whether a few days of lobbing cruise missiles at the Assad regime makes sense. If the US government (for good reasons) isn’t aiming missiles at Assad’s chemical weapons stockpiles, then what are its targets? How much damage can the US government realistically accomplish from ships in the eastern Mediterranean? If the strikes don’t effectively change the current status of Syria’s civil war, what point will they serve? Above all, if Assad can simply hunker down and reemerge after a few days of missile strikes, doesn’t that risk US credibility too? What kind of deterrent is a pinprick?

That line of questions has already opened the door to mission creep — former US defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld, who led the US war effort in Iraq, is calling Obama’s response ‘feckless and ineffective,’ and the Obama administration is reportedly planning an even more robust operation that would aid Syria’s anti-Assad rebels and provide US-led training in nearby Jordan.

That’s all a far cry from a no-fly zone or an international peacekeeping force or additional inspectors whose presence can dial down the atrocities of Syria’s civil war and ultimately help push both sides to a political settlement.

8. Could a strike against Syria destabilize Lebanon?

In his Senate testimony, Kerry argued that unless the United States acts, Assad might provide chemical weapons to Hezbollah, the powerful Lebanese Shiite political group and armed militia, which would threaten Israel. But if Assad were going to do so, wouldn’t it have been in the two decades when Hezbollah was working in southern Lebanon to push Israeli troops out of their territory? Wouldn’t he have done it during the war in summer 2006 between Israel and Lebanon? The result of that war was to force Israeli troops out of southern Lebanon, the impetus for Hezbollah’s creation in the early 1980s.

Hezbollah today is less focused on Israel and instead more focused on retaining its grip on power in Lebanon and boosting the Assad regime in Syria. If there’s a risk, it’s not that Assad will share chemical weapons with Hasan Nasrallah, the Hezbollah leader, who would be absolutely crazy to unleash chemical warfare on northern Israel.

The risk is that by endorsing the anti-Assad opposition, the United States will embolden Hezbollah to justify their pro-Assad efforts in the cloak of standing up to American power. Another risk is that by emboldening Hezbollah, the United State will encourage radical Sunni groups to increase their efforts on behalf of anti-Assad rebels. It’s easy to imagine that what have so far been isolated car blasts in Tripoli to Beirut could become daily occurrences. The Syrian civil war has already frozen in place the current Lebanese government and prevented any chance of passing a new election law and holding fresh elections. Lebanon is holding its breath, even while most of its political elite struggles mightily to tone down passions over a neighboring country that has long played an outsized role in Lebanese life and politics.

It’s all too easy to imagine various Christian Maronite groups, who have always been split between pro-Syria and anti-Syria factions, also join the fight. It’s easy to imagine the moderate Sunni leadership, including the relatively anti-Assad former prime minister Saad Hariri to the relatively pro-Syria Najib Mikati (pictured above left, with Hariri right), or even Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, forced to take sides. A return to civil war in Lebanon is in no country’s national interest — not the United States, not Lebanon, not Israel, not any Middle Eastern country, not any European country.

No one’s asking about this in the US debate, either because they don’t understand the complexities of Lebanese politics enough ask these questions or if they don’t care enough about tiny Lebanon to bother.

9. How will a strike against Syria affect US-Iranian relations?

The greatest irony of the past two weeks is the extent to which Iran and the United States see eye-to-eye on the use of chemical weapons.

Iran is no fan of chemical weapons because in the 1980s, Iraqi president Saddam Hussein used them against Iranian soldiers in the middle of an Iraq-initiated war shortly after the 1979 Iranian revolution that led to the establishment of the Islamic Republic. Even last week, we learned the extent to which the administration of US president Ronald Reagan knew of and acquiesced to Saddam’s use of chemical weapons against the Iranians in the 1980s.

Even while it weighs its options with respect to Syria, the United States has a national interest in resolving its decade-long conflict with Iran over the Iranian nuclear energy program and its suspicion that Iran is seeking a nuclear weapons program as well. The election two months ago of the relatively moderate cleric Hassan Rowhani, who came to power in a landslide victory after promising a more conciliatory tone with the United States and European powers in hopes of reducing the sting of economic sanctions on the Iranian economy, marked a new opportunity for US-Iranian relations, which have been strained since well before the 1979 revolution.

Even more remarkably, Iran’s entire governing class has responded to the growing escalation over Syria with impressive restraint — not only has Rowhani refrained from the kind of anti-American, anti-Israeli rhetoric that had become standard under his predecessor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, but his foreign minister Javad Zarif and Iran’s supreme leader Ali Khamenei, have all called for a peaceful resolution to the US-Syrian standoff, while condemning the use of chemical weapons by any party.

But the hardliners in Iran’s government haven’t disappeared completely, and a US miscalculation over Syria could bring them back into favor at a time when Iran’s moderates are otherwise ascendant. It wouldn’t be the first time the United States overlooked an opportunity for better relations with Iran, but it would be especially careless to throw away the best opportunity in 11 years for progress.

10. What, if anything, might lead the United States into a more long-term morass in Syria?

These are the dreaded ‘what if’ scenarios that must keep Obama awake at night.

What if Assad uses more chemical weapons, despite the US strikes?

What if the anti-Assad opposition gains access to chemical weapons and uses them in the future in retribution?

What if US and Russian ships in the eastern Mediterranean come to blows?

What if Assad actually manages to destroy a US warship?

What if Assad somehow finds a way to counterattack US citizens at home or abroad?

What if Assad holds on and wins the civil war?

What if Assad loses and some unknown Sunni government comes to power?

What if nothing happens and Syria remains divided into pro-Assad Alawite and anti-Assad Sunni (and relatively neutral northeastern Kurdish) enclaves?

What if a US attack helps propel Iraq back into sectarian violence?

And that’s just for starters — there’s no way to know what kinds of problems the United States could cause by introducing a new element into a such a dangerous situation. During the Iraq war, so many of the problems that would plague the United States in 2004 and later actually germinated in 2003 — a hesitant chain of command, the dissolution of Iraq’s military, the failure to deploy significant numbers of troops to guarantee security, the failure to foresee the rise of sectarian conflicts bubbling beneath the surface during the quarter-century of Saddam’s Ba’ath Party rule.

Any one or dozen or three dozen potential outcomes shouldn’t alone dissuade the Obama administration from taking any particular action. But there’s also no indication that the Obama administration has worked through the possible negative consequences of US military engagement, and what might follow.

2 thoughts on “Ten questions the United States Congress should be asking about Syria”