As the administration of US president Barack Obama begins to close ranks to secure the support of both houses of the US Congress, today’s big news on the escalating international crisis over Syria’s civil war didn’t come from the United States — it came from Iran.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

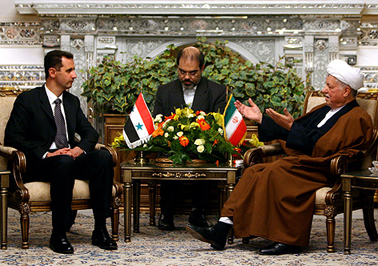

That’s because former president Hashemi Rafsanjani all but admitted that the government of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad (pictured above left, with Rafsanjani, right) was responsible for unleashing a chemical attack on his own people.

Even as US secretary of state John Kerry took to Sunday’s television news shows to announce that the United States had determined from hair and blood samples the presence of sarin gas in the chemical attack 10 days ago on the eastern outskirts of Damascus, a conclusion that United Nations weapons inspectors seem likely to confirm early this week, Rafsanjani’s admission (even if inadvertent) goes a long way in confirming that the Assad regime is indeed culpable.

As originally reported by the Iranian Labour News Agency, Rafsanjani all but indicated that blame lies with Assad and the current Syrian government in remarks that otherwise sympathized with the plight of Syrians after over two years of increasingly sectarian fighting and civil war:

‘The people have been the target of a chemical attack by their own government and now they must also wait for an attack by foreigners.’

‘Right now America, the Western world along with some of the Arab countries are nearly issuing a clarion call for war in Syria – may God have mercy on the people of Syria,’ he said. ‘The people of Syria have seen much damage in these two years, the prisons are overflowing and they’ve converted stadiums into prisons, more than 100,000 people killed and millions displaced,” he added.

A later version of the story slightly revised Rafsanjani’s quote, but it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that Rafsanjani was conceding Assad’s culpability.

Iran remains one of Syria’s top allies, both regionally and globally, largely because the Assad family are Alawite (a small mystical sect of Shi’a Islam) and have since the 1970s prevented the rise of a Sunni Arab state on Iran’s Western border, instead providing a reliable ally to Iran’s predominantly Shiite Islamic Republic. Even as Obama pushes for support within Congress, he is also likely to look for additional support from other Middle Eastern nations — Turkey’s patience with Assad ran out long ago, and the predominantly Sunni Arab kingdom of Saudi Arabia also backs a US military strike.

Rafsanjani, who served as Iran’s president from 1989 to 1997, is a relatively moderate voice in Iranian politics. Although Iran’s powerful Guardian Council disqualified him from running again in the recent July presidential election, Rafsanjani is very close to Iran’s newly inaugurated president Hassan Rowhani, who is also an Iranian moderate and has urged reconciliation with the United States and other Western countries.

While there’s no doubt that Iran, like Russia, will continue to support Syria, Rowhani’s remarks about potential US military action in Syria have been relatively tame. That’s great news for the Obama administration, given that Rowhani’s election two months ago provided the United States its best opportunity since 2002 (when former president George W. Bush included Iran in his ‘axis of evil’) to improve a tortured relationship with the Islamic Republic.

Although Iran has become a pariah state in recent years over its nuclear energy program (and the corresponding US and European fear that Iran is trying to develop a nuclear weapons program as well), many Iranians were the victims of the last major chemical weapons attack in the Middle East when Iraqi president Saddam Hussein deployed mustard gas and sarin against Iran during the Iraq-Iran war of the 1980s — with the knowledge and acquiescence of the United States, which wholeheartedly supported Iraq in the 1980s.

Rowhani made clear through his presidential Twitter feed this week that he condemned the use of chemical weapons, in Syria or elsewhere:

Iran gives notice to international community to use all its might to prevent use of chemical weapons anywhere in the world, esp. in #Syria

Javad Zarif, Iran’s new foreign minister, went even further in an English-language Facebook post (!) yesterday condemning the use of chemical weapons as well, while also pleading for the United States and its allies to work through the channels of international diplomacy and the United Nations:

Any use of chemical weapons must be condemned, regardless of its victims or culprits. This is Iran’s unambiguous position as a victim of chemical warfare. But has it always been the position of those who are now talking about punishing their presumed culprit? How did they react when civilians in Iran and Iraq were victims of independently established massive and systematic use of advanced chemical weapons by their then-friend Saddam Hussein?…

Are all options really on the table as the US president repeatedly declares? Is every nation with military might allowed to resort to war or constantly threaten to do so against one or another adversary? Isn’t the inadmissibility of resort to force or threat of force a peremptory norm of international law? Is there any place for international law and the UN Charter at least in words if not deeds?

Sure, Zarif is calling out the United States for its hypocrisy on chemical weapons less than three decades ago, and his warning for the world to ‘avert another catastrophic adventurism’ is a clear tweak of the US invasion and subsequent occupation of Iraq in the last decade. But given the histrionics of Rowhani’s predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the rhetoric coming from Tehran since the Syrian chemical attack has been extraordinary mellow.

Even Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who is certainly no moderate, held back on harsh rhetoric last Wednesday when he cautioned that a US military strike in Syria would be a disaster for the region.

That’s a good sign for US-Iranian relations, which still have the potential for a major breakthrough. Rowhani, who previously served as Iran’s first negotiator with the United States and other world powers over its nuclear energy program from 2003 to 2005, and who agreed to the conciliatory step of pausing Iranian uranium enrichment efforts, won a landslide first-rounf presidential victory two months ago with a pledge to lift international sanctions that are crippling the Iranian economy.

It would be wise for Obama to acknowledge the shameful double standard with which the United States essentially condoned chemical warfare in the 1980s against Iran. A likely US military strike against Syria won’t win the Obama administration any friends in Tehran and it could still embolden hardliners within Iran’s government, such as the Revolutionary Guards, at the expense of moderates like Rowhani and Rafsanjani. But the guarded response from Iranian officials indicates, at least so far, that a military strike won’t slam shut the possibility of improving US ties with Iran.

6 thoughts on “The big news on Syria this weekend? Iran’s surprisingly mellow reactions to US military plans”