Lurking behind the sexier issues at the forefront of tomorrow’s Québec provincial elections — sovereignty, federal-Québec relations, health care, corruption inquiries, tuition fees and student protests — lies an issue that will be quite strongly affected by who wins.![]()

![]()

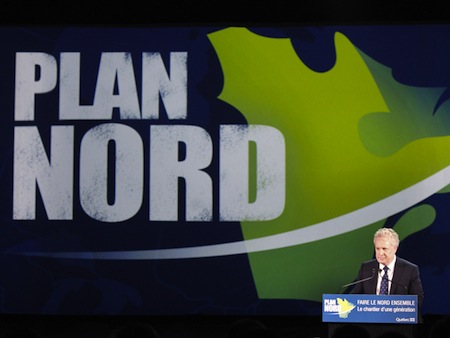

That issue is premier Jean Charest’s Plan nord — a plan announced in May 2011 to exploit the natural resources in the great expanse that comprises the northern two-thirds of Québec. The idea is that over the next 25 years, the Plan will attract up to $80 billion in investments for mining, renewable and other forms of energy and forestry. Charest, whose Parti libéral du Québec (Liberal Party, or PLQ) is struggling to win a fourth consecutive mandate, has made it one of his government’s top priorities, although it’s been met with some resistance from environmentalists as well as from the native Innu people, around 15,000 of whom inhabit Québec’s far north, to say nothing of Charest’s political opponents.

His government claims that northern Québec contains deposits of nickel, cobalt, platinum group metals, zinc, iron ore, diamonds, ilmenite, gold, lithium, vanadium and rare-earth metals, and that, with a warming climate and melting polar ice, extracting the mineral wealth will be easier than in past generations. The region, although fairly undeveloped and remote, already produces 75% of hydroelectric power in Québec.

François Legault, the leader of the newly-formed Coalition avenir Québec (CAQ), has argued that Charest’s government is “putting all its eggs in one basket” with Plan nord, but he hasn’t said he wants to scrap it — he’s criticized Marois as well for trying to extract more royalties from mining companies. Legault has proposed using $5 billion from the province’s $160 billion Caisse de depot et placement (its public pension fund) to capitalize a new natural resources fund.

In announcing Plan nord, Charest stressed the developmental elements of the plan, which would include a $2.1 billion investment from the province in northern infrastructure and which would also aim to build roads to link communities — in many cases, for the first time.

He also stressed the conservation elements of the plan — the government has claimed it will set aside 50% of the region for natural protection and unavailable for industrial development.

Late last week, however, Charest’s PLQ was ranked the worst of the three parties for the environment in a survey among environmental groups — a fourth party, the leftist and sovereigntist Québec solidaire, scored the highest with 83% under the survey, while the Liberals scored just 33%. The report followed another news story in Le Devoir late last week that claimed the Plan nord would wipe out wild caribou herds in the region.

Meanwhile, it is not clear that Charest has ever had the native population, which owns much of the land and mineral rights, quite on board. Also last week, Ghislain Picard, Grand Chief of the Assembly of First Nations of Quebec and Labrador, criticized the Charest government in a criticized the manner in which the Charest government has approached northern development:

In an open letter published Wednesday, Picard said, “To put it bluntly, we have hit a wall! It became obvious to us, and quickly, that Jean Charest wanted to talk about the territory only according to his particular terms,” Picard said. “As soon as we tried to address the issue of the territory on the basis of principles having been the object of a consensus amongst the First Nations, such as the co-management of the decision-making process, development, consultation, sharing of revenues, we were flatly turned down.

“From that moment, the process for which we had high hopes came to an abrupt end and was replaced by a dialogue of the deaf.”

Hardly a vote of confidence from a group that must be a partner if the Plan nord is to succeed — and the PQ and CAQ hardly seem better (if anything, the PQ would require more French language hurdles with which miners, native groups and developers will have to comply).

Although Québec is a relatively wealthy place in the global scheme of things, its GDP per (around $40,000) falls behind that of the average Canadian GDP per capita ($48,000), which belies the disparity of relatively wealthier, mineral-rich provinces like Alberta (GDP per capita of $70,000) and relatively poorer provinces like Nova Scotia (GDP per capita of $38,000) and Québec. If Plan nord succeeds and truly significant minerals or energy are extracted, it could transform Québec into an eastern version of Alberta, generating flush amount of private and public revenue.

By way of comparison, Ontario — which has a little over 1.6x the number of people as Québec — has an economy nearly twice as large as Québec’s. Ontario’s economy is roughly equivalent to the size of Switzerland’s economy (if it were independent, Ontario would have the world’s 25th largest economy), while Québec’s economy is equivalent to that of Venezuela.

Over the 20th century, Montréal, once the financial capital of Canada, withered as Toronto grew into its own, with business interests hesitant to invest in Canada following the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s that polarized the province into separatist and federalist factions. The activist state interventionism of Québec’s provincial government, which nationalized the province’s electric industry in the 1963 (today, Hydro-Québec still has a monopoly on electricity) played a role in pushing investment out of the province, to say nothing of the strict French-language requirements codified in Bill 101, passed in 1977, that made French the official language in Québec, and required all businesses to use French for their affairs in the province.

Photo credit to Mathieu Belanger, Reuters.